Remembering the 1826 Weavers Uprising in East Lancashire

This blog has been written by Dr David Scott. David works at The Open University and is a world leading expert in the field of Criminology. He is the founder and chair of the Weavers Uprising Bicentennial Committee.

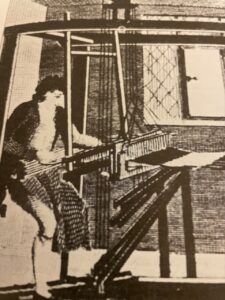

Handloom weavers in the nineteenth century were known to be a hard-working and compliant workforce who faced periodic poverty with stoical resilience. Yet in east Lancashire in April 1826 their patience clearly broke. Faced with a perfect storm of high food prices, low or no wages, the accumulative impact of poverty over several years and the introduction of much cheaper forms of weaving through powerlooms in the factories, the handloom weavers and other ordinary people felt they had no choice but to respond to the very real threat of mass starvation and related illnesses and premature deaths with rebellion. The significance of the events of April 1826 have though been largely forgotten and so a new charity has been formed – The Weavers Uprising Bicentennial Committee – to work towards the remembrance of the context, happenings and aftermath of the weavers uprising.

The Weavers Uprising

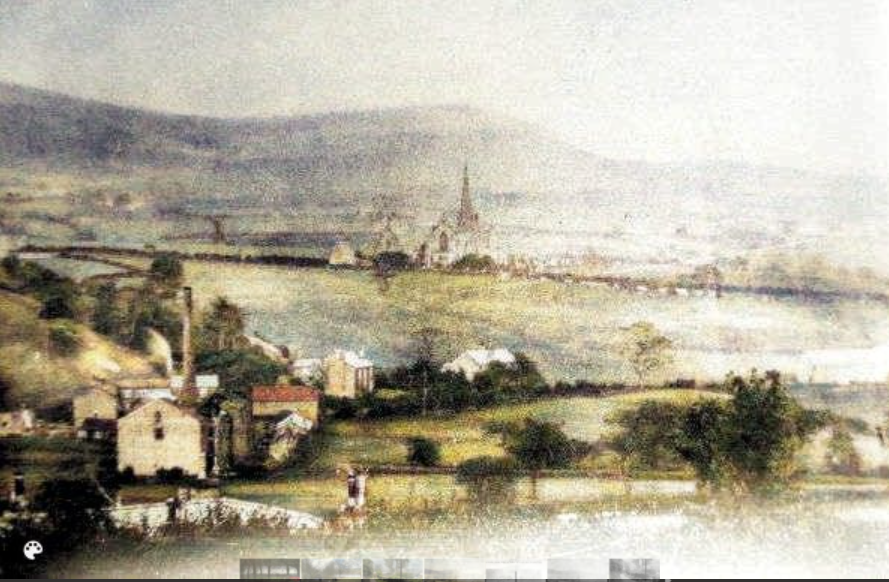

On the morning of the 24th of April 1826 thousands gathered at Whinney Hill, near Accrington, to devise a desperate plan of action in the face of starvation. Their mission was clear – to destroy all the powerlooms in east Lancashire without the unnecessary destruction of property or any violence to the person. During the uprising more than 1,100 powerlooms were destroyed by weavers and their associates. From Whinney Hill as many as 10,000 people are believed to have joined the crowd as it headed west towards Oswaldtwistle and Blackburn. On the following day, 25th of April 1826, around 2,000 protestors gathered in Earcroft and marched through Lower Darwin and Hoddlesden and then over the moors to Helmshore an eventually Haslingden. Their intent was a focused destruction of the powerlooms as a means of sending a political message about their extreme poverty,

On the third day of the uprising, the 26th of April 1826, the soldiers were ready for the protestors. That morning a crowd, estimated of between 3,000 to 4,000 people, made their way from the adjacent towns of Haslingden and Rawtenstall along the sides of the south Pennine moors to Dearden Clough Mill in Edenfield and then down the steep hill towards the mill at Chatterton. When they arrived at Chatterton Old Lane, the local magistrate and the soldiers were waiting for them. Not long before 11am, the local magistrate, William Grant, read a short extract from the 1714 Riot Act.

Shortly afterwards, under the orders of Colonel Kearney, 20 riflemen from the 60th Duke of York Own Rifles lined up in two ranks of 10 at the bottom of Chatterton Old Lane and opened fire. The soldiers fired 600 bullets into a crowd of 3,000 people over a period of 15 minutes. In the chaos that followed at least six people were shot dead – James Lord, John Ashworth, James Rothwell, Richard Lund, Mary Simpson and James Whatacre – in what can only be truly described as a massacre. Remarkably, following the killings the protestors regrouped and continued their quest to destroy further powerlooms. The final day of the uprising, 27th of April 1826, started with just a couple of hundred people, but as the protestors made their way from Tockholes to Water Street Factory in Chorley, they were joined by a large crowd of bystanders.

The Aftermath

The response of the state to the uprising and food poverty in east Lancashire was punishment. This punitive mentality can be witnessed from the demands of the then Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel, that none of the protestors should receive any of the charitable relief organised in London from May 1826, through to the harsh punishments received by protestors at the Lancaster Assize later in the year. Thomas Ashworth, who was one of the protestors in the uprising, died on the 26th of September 1826 from a ‘visitation of God’ (heart attack) after receiving the death penalty for his part in the uprising. A total of 41 protestors received the death sentence, and whereas 31 of those were later commuted to prison sentences, 10 people who were part of the crowd during the uprising were transported to Australia.

Even worse, the mass deaths that the weavers had feared and hoped to prevent, especially of children, were not avoided. Ongoing research has uncovered many hundreds of child deaths in the year following the uprising. The abject failure of the government to intervene means that these deaths can be understood as a form of social murder (when social conditions generate death rather than life).

The Bicentennial Committee

A new Weavers Uprising Bicentennial Committee was launched during the inaugural weavers uprising remembrance walk at Whinney Hill on the morning of 24th April 2022. The inaugural walk covered approximately 45 miles over five days and (broadly) followed in footsteps of handloom weavers. On 26th April a wreath was laid to commemorate the six people who died at Chatterton and those who died later of social murder.

Over the next three or so years, the bicentennial committee aims to work for the public benefit in preparation for the 2026 bicentennial of the uprising. Its official ‘objects’ are to:

- Organise commemorative events, artwork, music, guided walks, remembrance walks, talks and other cultural events

- Initiate new research and educational resources for local people (adults and children) about the uprising and its context

- Create a sustainable legacy by securing funding for appropriate forms of remembrance

The Bicentennial Committee is currently engaging with local councils, MPs, museums, heritage societies, universities, newspapers and other local groups to help generate interest for the 2026 commemorations.

If you would like to know more about the massacre, including conditions that led to the uprising, further details of the the inaugural remembrance walk, and why this tragedy has for so long been either misinterpreted or forgotten, click here.